The Rowing Life – Boats Of Whitby

A.F. Humble

The following text is reproduced from a detailed story of rowing lifeboats that have served at Whitby, written by A. F. Humble in 1974. It is presented here to give the reader an insight into many of the gallant rescue attempts made by Coxswain Thomas Langlands and the brave volunteer lifeboatmen of Whitby.

Part One

Coxswain Thomas Langlands

Henry Freeman, coxswain of Whitby No. 1 lifeboat for more than 22 years, retired at the end of September 1899. The local Committee appointed as his successor Thomas Langlands, who had been coxswain at Upgang for nearly a quarter of a century.

Langlands was a Northumbrian, born at Seahouses in 1853, but educated at the Mount School, Whitby. At the age of 18 he had joined the Whitby lifeboat crew: two years later he became second coxswain at Upgang and in 1877 was appointed coxswain there, at the unusually early age of 24.

When Langlands first went to Upgang, sail was still dominant at sea. Huge fleets of collier brigs, schooners and ketches could be seen from the Whitby cliffs, carrying coal from the Tyne ports to London. These vessels, heavily laden and often badly maintained, suffered appalling losses during bad weather. A winter gale could drive scores of them ashore in a single night. The fortunate ones were carried high up the beach at the top of the tide; and the crew might then be rescued from the shore, but many struck at low water and were gradually battered to pieces as the tide rose. It then became the task of the lifeboat to cross the intervening stretch of broken water and take off the crew, before the wreck broke up or the men were swept away as the waves broke over the ship. This problem had confronted successive generations of lifeboatmen how to rescue men from a grounded vessel which was breaking up under the battering of heavy seas. All the spectacular rescues at Whitby had been variations on this theme the "Smales" in 1830, the "Jupiter" in 1838, the "Wrangel" in 1849, the wrecks of 1861 and that of the "Royal Rose" in the following year. Langlands himself had attempted such a rescue when the "Lumley" was lost in 1881, and a few days later Freeman had been successful in saving the crew of the "Visitor" in very similar circumstances.

The Upgang Station had been founded in 1865 to ensure that a lifeboat was available to go to the aid of vessels aground on Whitby beach even when it was impossible to launch from the slipway or from the harbour.

Towards the end of the century, beach rescues became less common. Steam was rapidly replacing sail in the coasting trade, and fewer vessels were driven ashore by stress of weather. The service boards kept in the Life-boat Museum record the occasions on which the boats were launched to save life, and show that after 1880 the proportion of rescues from beached craft fell rapidly, while the proportion of services to fishing craft rose. Nevertheless, with his experience of beach rescue work, it is not surprising that on his appointment Langlands examined the Whitby boats with their suitability for beach work in mind.

Evidently he was not satisfied with the No. 1 boat, the "Robert and Mary Ellis". Her crew did not like her. She had been criticised as being too heavy when she was entered for races in the Regatta, possibly Langlands thought she was heavy on service. The boat had been supplied in 1881: in 1900 the District Inspector of Boats recommended that she should be replaced. After some discussion, the local Committee expressed the opinion that there was no need for a new boat and suggested that the old one should be kept "for service to cobles".

Traditionally this had been the function of the No. 2 boat which at that time was the five-year old "John Fielden". It seems that the Committee felt that the ten-year-old "Upgang" with the "John Fielden" would be adequate to deal with emergencies on the beach, and that the Inspector's unfavourable report on the "Robert and Mary Ellis" could be ignored. For the moment Langlands could do nothing, but in 1903 he persuaded the Committee to sanction an improvement in the self righting powers of "John Fielden" by modifying her water tanks.

Early in 1904 the local Secretary, Captain Gibson, retired. He had been decorated for long service a few years earlier. His successor, Mr. J. W. Foster, faced two very serious problems at his first Committee meeting. The road from the lifeboat house to the beach, down which the boat had to be taken for launching, was in a very bad condition. Some members maintained that unless it could be repaired it would be necessary to close Whitby No. 1 Station. Correspondence with R.N.L.I, headquarters in London followed. Mr. Foster explained that the slip-way, or as he called it, the cart track, belonged to the Harbour Commission, which he described as an impecunious body.

However, the Harbour Trustees contributed £5.5.0 towards the cost of repairs, the Urban District Council ultimately gave £20, and the Institution paid the remainder of the bill. The other problem, the dislike of the crews for the "Robert and Mary Ellis" was considered, but no action was taken, though it is noticeable that in 1907 the Committee agreed that during the winter months she should be moored in the harbour and operated from there. In effect, though not in name, she had become the No. 2 boat, used mainly for assisting the fishing fleet.

While he had been coxswain at Upgang, Langlands had rarely been called upon to assist cobles in difficulties. At Whitby the situation was very different. The harbour bar could be very dangerous, and the entrance to the port was so narrow that in rough weather sailing vessels anchored in Whitby Roads rather than risk coming in between the piers. In January 1900 three local colliers the "Maria", the "Alert" and the "Gem of the Ocean" sailed for the Tyne. Next morning they had to put back because of contrary winds. In a strong N.W. wind and a heavy sea, they attempted to anchor off Sandsend, rather than risk trying to enter the port. When their anchors began to drag, the "John Fielden" was launched, but the colliers got in without assistance. An entrance which coasting craft avoided in rough weather was certainly dangerous for cobles in bad conditions.

A month later another dangerous situation arose. Early in the morning the fishing fleet put to sea in fine weather. Later in the day, watchers ashore noticed that the weather was deteriorating and that the boats had abandoned their fishing and were heading for home. The bar looked dangerous: the rescue services were warned and took such precautions as they could. The "John Fielden" was launched and stood by off the harbour mouth. The Rocket Brigade prepared to put a line between the piers so that life-buoys could be lowered to men whose boat might overturn as she came in. Sixteen cobles were heading for the port, their sterns low in the following sea. Three of them came in safely, the remainder turned away and ran for Runswick, rather than risk the dangerous entrance to the harbour. The "John Fielden" was brought back to her shed, having to the casual observer, accomplished nothing. Nevertheless, her assistance might have been invaluable, as Langlands himself had good cause to realise a few years later.

Once more the fishing fleet put to sea in good weather. Once more the boats were caught by a sudden gale, and headed for harbour. There was a stiff N.E. wind, and the harbour bar felt the blast at its strongest. The tide was ebbing but the sea was making in a very ominous fashion. Huge rollers hurled themselves on the beach and on the pier ends, and there was in addition a heavy ground swell.

Langlands coble, the "Thankful" came in safely, but the "William and Tom" which followed her was not so fortunate. Her crew were washed out of her. Langlands, seeing the danger, turned and re-crossed the bar, and was able to pick up two of the men. The third swam to safety. Langlands now had five men in a coble built for three, but the "Robert and Mary Ellis" under the Upgang coxswain put out from the slipway in time to take on board the men from the wrecked "William and Tom" and also the three men of the third coble, the "Jane and Mary" which was later washed ashore, stripped of her catch and all her gear. Langlands did not attempt the entrance again, but ultimately landed safely at Runswick. The incident was much more serious than the previous one, but the basic similarity of the two emphasised the need for the lifeboat to stand by when the cobles were coming in before a gale. For his courage in re-crossing the bar to help the crew of the wrecked "William and Tom", Langlands was awarded the silver medal of the Institution.

|

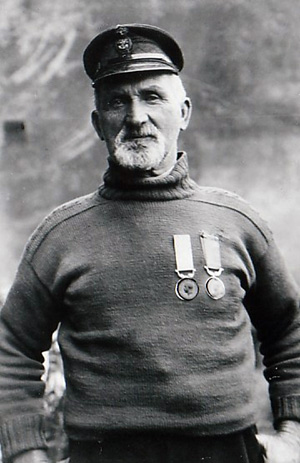

| The Whitby lifeboat Robert and Mary Ellis and her crew |

Such rescues as these are typical of the services rendered by the lifeboats to the fishing fleet. Sometimes a vessel would run ashore on the beach and assistance would be given by the Upgang boat or by Whitby No. 1. There was very thick fog on 31st May, 1902. A schooner struck Whitby Rock, the "John Fielden" went out to give assistance, but during a break in the fog a steamer was able to tow the schooner off. Just how bad conditions were, may be judged from the experience of the crew of the S.S. "Ben Corlic" of North Shields on the same day. Off course in the dense fog, and unseen from the shore, she struck the rocks at Upgang and was badly damaged. One of her boats capsized, throwing eight men into the sea. Four were picked up, two were washed ashore, and two were drowned. The second mate's boat was driven back to the steamer, but another came to the beach near White Point. The Chief Engineer gave the alarm. The five men on the steamer were saved by the Upgang boat, the chief difficulty being caused by the fog rather than by rough weather.

A similar incident took place in January 1904, when a London steamer of 1,025 tons, variously described as the "Kaifong" and the "Cayo Benito" ran aground near Upgang on a calm and starlit night, but with occasional fog. The Whitby No. 1 boat was launched quickly but the Upgang boat was not so fortunate, for as she was being launched she was swung broadside to the beach by the tide and heavy waves. Eventually her crew got her afloat and shared with the "Robert and Mary Ellis" in saving the steamer. The affair made it clear that although it was desirable to maintain a lifeboat at Upgang, launching there could be very difficult.

It was many years since a violent gale had covered the beach with wreckage from stranded ships, flung ashore by winds which tore the sails to ribbons, and by waves which battered the hulls to pieces. Steamers were usually able to keep well clear of the coast, and were less liable to being driven off course than sailing craft had been. The change brought about by the coming of steam was unmistakably demonstrated in March 1906, when a tremendous gale from the North, combined with a heavy Spring tide, produced conditions which in earlier years would inevitably have caused appalling losses amongst the collier brigs.

In the words of an eye witness, "The force of the wind seemed to

hold the water up, and huge breakers were formed when the oncoming waters

found something approaching a bar to their progress at Whitby Rock:

"Close inshore the spectacle was wild in the extreme. Huge breakers

towering high in the air broke on the ends of the piers, and dashed

with vehement force against the lighthouses and as the tide rose these

breakers increased in volume, and beat remorselessly against the substantial

structures. The harbour bar was a vortex of turbulent and raging waters.

The seas rose to the height of the piers, breaker succeeding breaker

with never a moment's pause. The East Pier was quite overwhelmed by

the torrent of waters; huge waves broke over it, sweeping its entire

length and covering it with foam, as though it were a country hedge

in drifting snow".

The storm must have been one of the worst ever known at Whitby, yet no ship was lost off the port, and the lifeboats remained in their sheds. It was obvious that rowing lifeboats would have been of little use in such a storm, and men must have wondered whether even the steam lifeboats with which the R.N.L.I, had been experimenting, would have survived such conditions.

The rowing lifeboats proved their worth a few months later when the Newcastle steamer, "Isle of lona" struck Upgang Rock in hazy weather, and then ran aground some 300 yards south of the East Pier. The two Whitby boats saved all 17 men of her crew. More exciting, and very similar to some of the incidents of the days of sail, was the successful attempt of the steam launch "Osprey" to enter the harbour in boisterous weather. The sea was very rough, and it was made worse by a sudden squall. The crew of the Upgang boat went to their station accompanied by a large party of launchers. By the time the lifeboat was on the slipway, the "Osprey" had turned away from Upgang, and was making for Whitby. Pounder Robinson, the coxswain, realised that it was useless to launch, as the "Osprey" would be at Whitby before he could get through the broken water. Langlands, watching from the Spa grounds, at first mistook the "Osprey" for the Runswick lifeboat, but when he recognised the facts he proposed to bring out the "John Fielden". Unfortunately most of his regular helpers were at Upgang, and an excited crowd tried to haul the boat to the beach. They jammed her against the door frame of the boathouse, then nearly ran her into the bandstand. Shouted orders could not be heard in the confusion, but finally the boat was launched just before the "Osprey" made her own way into the harbour. The incident was an excellent example of the difficulties which could arise if too many experienced lifeboatmen and helpers went to Upgang, leaving the Whitby station undermanned and without sufficient officers. The R.N.L.I. did what it could by having a telephone installed at Upgang, but the station was never easy to operate.

In the following year (1908) the "Robert and Mary Ellis" was condemned, and replaced by a larger boat of the same name. At the same time a new boat was supplied for Upgang. As yet motor lifeboats were few in numbers; it is interesting to notice that rowing boats were still being built ten years after the second "Robert and Mary Ellis" was sent to Whitby. February 1909 saw a beach rescue of the old type, carried out with the customary courage and skill. The ketch "Gem of the Ocean" which had sailed in and out of Whitby harbour ever since 1856, had left Hartlepool at 11 a.m. on February 15th, in fine weather. About noon, there was a sudden change. A northerly wind arose, the seas became very heavy and there were signs of an approaching storm. At 4 p.m. Kettleness coastguards reported a vessel in distress: Robinson and his crew went to Upgang and brought the boat out, taking her along the beach towards Whitby to intercept the "Gem of the Ocean". The latter, having weathered Upgang Rock, made for the beach, or rather was driven towards it, for the two men of her crew could not stand at the wheel and were seen rushing to the rigging at the onset of heavy seas. Eventually the ketch struck between the Spa and the Hotel Metropole, about two hundred yards out, and immediately swung broadside to the beach. The tide was low. Such a situation had been seen many times on that stretch of sand a vessel driven ashore in a storm, in danger of being submerged and broken up as the tide rose. The lifeboat was launched, and with great difficulty made her way through heavy seas to the wreck.

A line was flung aboard, but the lifeboat could not be brought close to the wildly pitching "Gem". Two of the lifeboatmen were almost swept out of their boat, which several times was gunwale full. At last one of the "Gem's" crew jumped into her. The boat had been damaged, several oars were broken, and most of the crew had been knocked into the bottom by the heavy seas, at times being in greater danger than the man left on the wrecked ketch. At last the boat was beached. Despite a broken rudder, she tried again. She was almost successful but was swept North of the wreck by the violent current. By this time Langlands had the Whitby boat on the lee side of the wreck, and managed to save the remaining member of the "Gem's" crew. A quarter of an hour later the masts snapped, the vessel went to pieces, and by morning the wreckage had disappeared.

Both coxswains well deserved the official "Thanks of the Institution inscribed on vellum", presented to them by the Archbishop of York at a ceremony held two months later.

The second instalment of the detailed biography of Coxswain Thomas Langlands can be accessed using the link below.

Please note, in the book "The Rowing Life – Boats Of Whitby" the text did not contain the photographs which I have added to complement the original text

© A.F. Humble, M.A. 1974