The British Steam Navigation Company

1856 - 1971

including the end of "The Raj at Sea" fifteen years later

A short history

By

David J. Mitchell

B. I. Engineer Officer

(1967 - 1974)

This short history was written for the families in British In ida Society and published in their journal in two parts. The first, 1856 - 1914 in No.11, Spring 2004, the second, 1914 - 1971 in No. 12, Autumn 2004.

I readily acknowledge the various sources of information as listed and the contributions made to B. I. by all those who served making it the greatest shipping company this country has ever had in its history.

Part One, 1856 - 1914

The Beginning

Quite whether William Mackinnon and Robert Mackenzie had a vision of the commercial empire that was to come from the business they founded in December 1847 in Calcutta, is a thought to mull over. These members of the Free Church of Scotland were to establish a formidable trading concern which within thirty years was well on its way to being an unquestioned success. The creation of one of, if not, the greatest shipping company to fly the Red Ensign in the history of British mercantile trading owes its start to their commercial acumen and astute political vision coupled with a fair amount of being in the right place at the right time.

It is fair to say The BI (as it will be referred to from now on) was throughout its history virtually unknown in the UK with Cunard, White Star, Orient, P&O, Union Castle, and Canadian Pacific amongst other shipping companies trading from the UK more likely to fall from the lips of those asked to name a famous line. Undeniable and undisputed is the way in which The BI played strategic and commercial roles in meeting British needs east of Suez from its founding in 1856, to the post 1945 collapse of Empire, and the years that remained until its demise in 1971. There are no points to score in this brief history. There are those who would wish to rewrite history to fit their concept of political correctness. Unfortunately I have no truck with this. Here is The BI as it was.

The early history of Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co. was clouded by the loss of Robert Mackenzie with the vessel Aurora shipwrecked off the Queensland coast on the 15 May 1853. He had been to Australia to seek out trading opportunities for the business of MM&CO (as the founding company will now be referred to) that had been trading from Calcutta to the UK, Australia and China from about 1849 using owned and chartered vessels. Both he and partner William Mackinnon were born in Campletown on the Kintyre peninsular in Argyll, and in 1847 they set up MM&Co in India as general merchants, with Mackinnon trading from his base at Cossipore and Mackenzie from Ghazipur.

The potential commercial opportunities in the sub continent were not going to be taken advantage of by the expansion of the railway network alone so sea borne trade around the Indian coast appealed greatly to MM&Co. Using the new fangled “screw steamers” would allow ships to be in and out of port as trade demanded without having to be dependant upon the wind blowing to fill sails. This would ensure a predictable time tabled service with all the benefits of reliability to be made available to merchants and traders, taking in the small ports from Calcutta, down the Malabar Coast, round Cape Comorin and northward to Bombay. Indeed the decision to use the propeller as the means of propulsion was well in advance of conventional thinking. To assist in running the business Mackinnon brought relatives and friends from Scotland out to India and in 1856 came the opportunity that was to lead directly to The British India Steam Navigation Company.

At this time, The Honourable East India Company was still the effective government of Burma and it put out a tender for a contract to carry the mail between Rangoon and Calcutta. In anticipation of this expected development, The Calcutta and Burma Steam Navigation Company with a capital of £20000 had been registered on 24 September 1856 in Glasgow and took as its emblem the Peacock of Burma. Two second hand ships were quickly acquired, Cape of Good Hope a 500 ton steamer rigged as a brig and the Baltic, a similar vessel of 536 tons and some 180 feet in length. For a colour scheme black was chosen for the hull with a white band. The funnel also was black with two narrow white bands separated by a thin black band. With the mail contract duly acquired, Cape of Good Hope commenced revenue earning service by sailing from Calcutta on 23 March 1857.

The regular routine of trips up and down the Bay of Bengal had barely begun when Cape of Good Hope was caught up in the Indian Mutiny and requisitioned by the Bengal Government to undertake trooping duties. Despatched to Colombo on 4 June 1857 she returned to reinforce Calcutta with six companies of the 37th Regiment of Foot (to become the 1st Battalion The Royal Hampshire Regiment). Thus started BI’s connection with trooping that was to continue until the cessation of sea transport in 1962. The utilisation of ships to carry troops was to play a significant part in future BI ship designs with holds designed to take troops, equipment and four-legged transport.

It took seven months for the Baltic to reach Calcutta in July 1857, and after being joined by Cape of Good Hope at the conclusion of her government service, dropped into the fortnightly mail routine. Passenger and cargo carrying trade soon developed and Rangoon was in time to become second only to Calcutta in importance with eight different mail and passenger services using the port and at least one ship going in or out every day but Sunday. The church upbringing of the founders dictated Sundays were rest days. At sea, Company service regulations required “Divine service to be held in the saloon or on the quarter deck every Sunday forenoon at five bells, circumstances permitting.” For the non-nautical types, five bells in ten thirty. Commanders were also “requested to say grace before meals.”

Logistics and Expansion

The bold decision to use screw propelled vessels from the start was taken with the knowledge that steam engines at that time were inefficient, consumed large quantities of coal, and stocks would have to be established at suitable locations. The Bengal coalfield provided the raw material and to meet requirements at the Burma end of the run, coal hulks were put in place at Rangoon with colliers chartered to bring in supplies. The original thinking to trade round the Indian Coast was gradually being implemented with ships venturing south of Rangoon towards Pengang and Singapore, and round Cape Comorin to Bombay and Karachi. The appearance of ships at the small coastal ports brought about a commercial revolution. Commanders of BI ships were made aware they were needed by the putting up of coloured umbrellas at a vantage point on the beach. Hence the BI ships became known as “Chatri Ki Jahaz” – the umbrella ships.

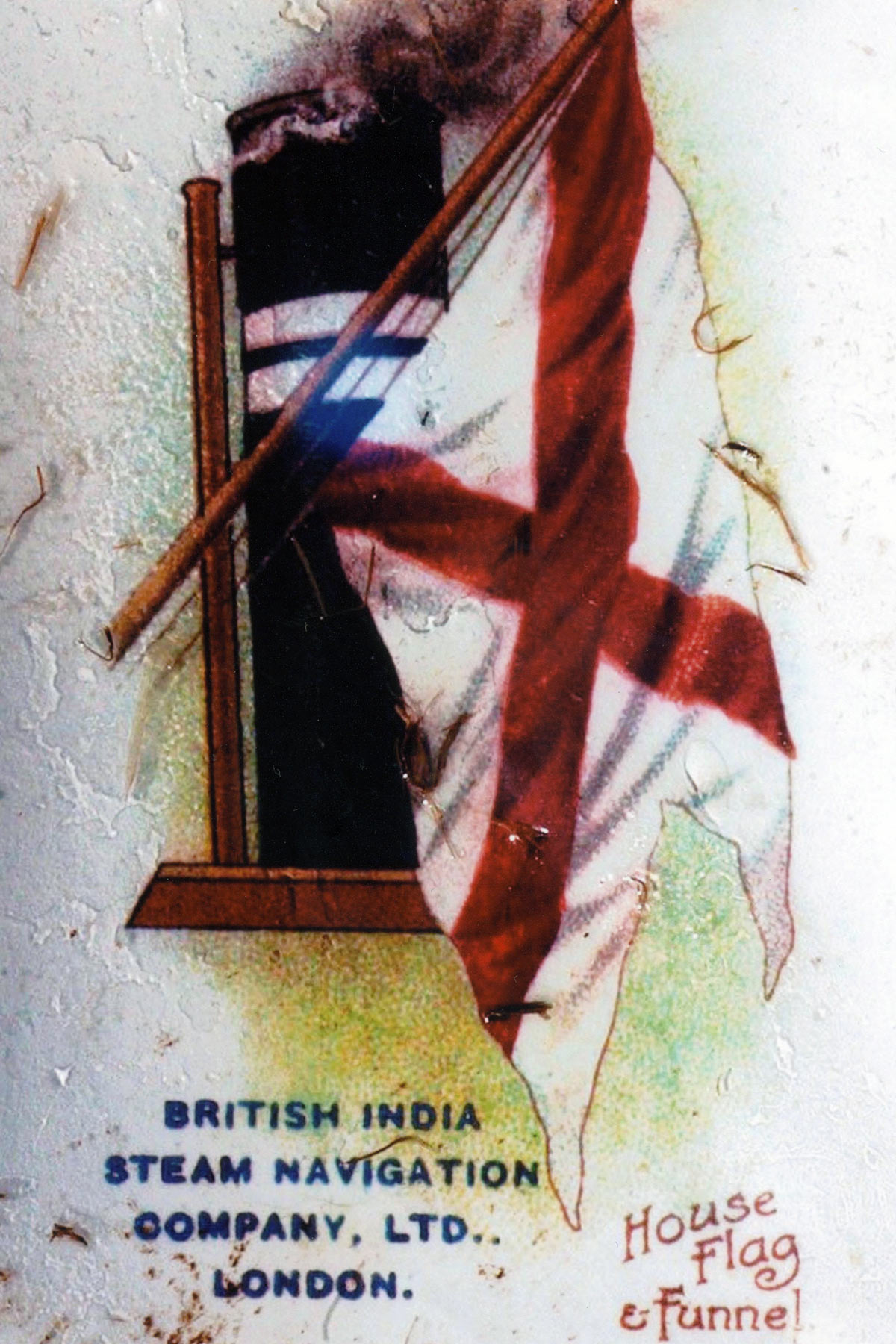

The first attempt to introduce a new regular service, Calcutta – Madras, as opposed to casual trade, in the 1860, unfortunately failed, but Mackinnon’s political connections lead directly to a Government of Bombay subsidy to run a Bombay-Karachi mail service fortnightly, and a Bombay – Basra mail service, initially on a six weekly timetable, being awarded in 1862. To meet this need, Mackinnon returned to the United Kingdom to raise more capital and quickly succeeded. On 28 October 1862 the British India Steam Navigation Company Limited was registered in Glasgow with a capital of £400,000; the assets of the Calcutta & Burma Steam Navigation Company absorbed into it. This entailed a change in company markings. Whilst retaining the same hull and funnel colours, the emblem became Britannia backed by the Lion, its paw on the globe, and the horse flag a St. Patrick’s Cross on a white ground, swallow tailed. Or in the language of heraldry, “On a burgee argent a saltire gules.”

Further mail contracts followed, Bombay-Calcutta and Madras-Rangoon. The liner mail service from Bombay up the Persian Gulf begun in 1862, was to be one hundred an twenty years later the finale of the BI when Dwarka performed the last rights and brought down the curtain on this astonished shipping company. To attend company affairs, agents were established and appointed in major ports. Uniforms became compulsory for sea going officers in 1863, and eventually crew alike. This visual enforcement of an organisation which knew what it was about had a profound effect upon shore side observers. As the company stature grew, the Serang or Boatswain would bring relatives and fellow villagers with him to make up his own crew. This arrangement fostered continuity and was maintained well after Indian Independence. It also generated an unsurpassed company “esprit de corps” which lasted to the end of the BI. From two ships in 1856, such had been the expansion of the company into the open arms of a receptive market that the fleet numbered twenty one vessels at the end of 1864. This strength enables nine ships, some with a sailing ship in tow, to transport the Indian army contingent to the Abyssinian campaign in 1867.

A not insignificant problem in the early days was a complete lack of adequate charts, navigational aides, marked passages and unlit coasts, therefore to eliminate future problems, the BI itself put in buoys, markers, and lights. Not until 1911 for instance, did the government of India take over from the BI the responsibility for upkeep and maintenance of lights and buys in the Persian Gulf. On top of this the weather had to be coped with, particularly the extreme cyclonic storms in the Bay of Bengal in the days when forecasts did not exist. Persian Gulf pirates presented another hazard. After one looting in the 1860’s the Sheikh of Muhommerah who was a friend of the BI hunted the miscreants down and recovered much of the gold taken from the ship. In recognition for many years after, every BI ship fired a salute as it passed his palace near Abadan.

The Suez Canal – Gateway to the East

No single event in the 19th Century was to have the economic effect the opening of the Suez Canal had. With the major part of the Empire east of Suez the advantages in communication and transportation of goods were enormous. The BI soon took advantage and within three months of the opening on 17th November 1869 a fully laden India, built as recently as 1862, was on her back to be re - boilered and have the engine compounded by her builders, Denny & Co. Dumbarton. Such were technical advances that her coal consumption would be halved making routes viable which were hitherto uneconomic. These factors of geography and economy would see the BI expand at a phenomenal rate in the next decade and a half. In the same year as Suez opened, the BI secured a major coup by taking the UK India trooping contract from the P&O using the 1867 built Dacca. The multi intertwining of government mail and trooping contracts with BI commercial interests went from strength to strength. This was more of a partnership with the BI ready at the drop of a hat to provide ships to meet the needs of the Empire. By 1873 the company boasted thirtyone vessels in service. In size they ranged from the 323 ton Moulmein dating from 1861 to the 1764 ton Patna built in 1871. To be delivered in 1874 were eight new vessels, four of them giants at just over 2000 tons each.

Services between London, Aden, Karachi and the Gulf (Basra) / Aden and Zanzibar connecting with London steamers / London and Zanzibar (irregular) / Europe jointly with the P&O / and Eastward to Singapore all operated by 1875. The 1880 handbook listed the following "Lines In Operation" around the coast:

| 1. Calcutta, Chittagong, Akyab and Kyoung Phyoo | Fortnightly |

| 2. Calcutta, Akyab and Ranoon | Fortnightly |

| 3. Calcutta, Rangoon, Moulmein | Weekly |

| 4. Calcutta and Straits via Rangoon and Moulmein | Fortnightly |

| 5. Rangoon and Moulmein | Four Weekly |

| 6. Rangoon and Moulmein | Weekly |

| 7. Calcutta, Port Blair, Camorta and Rangoon | Four Weekly |

| 8. Madras and Rangoon | Fortnightly |

| 9. Calcutta and Bombay, coasting | Weekly |

| 10. Bombay and Kurrachee | Bi - weekly |

| 11. Bombay and Persian Gulf (also calling at Kurrachee) | Weekly |

1881 saw a Bombay-Delagoa Bay (Lourenco Marques) service started and in the same year access to the Queensland coast to Brisbane was acquired. As a deliberate policy, ship construction allowed them to be suitable for all routes operated so in the event of a trooping charter arising, continuity of services could be maintained by moving vessels around. In the years after the Abyssinian campaign and prior to 1885, a total of twentynine ships served the military in the Perak Campaign, the Russo-Turkish War, the Zulu War, the Transvaal War, Egypt, and the Gordon Relief Expedition.

In the later part of the 19th century Indian labour was extensively employed in Burma, Malaya, in the Gulf and later in East and South Africa. To cater for the movement of humanity and its possessions, the BI developed ships capable of accommodating large numbers of deck or unberthed passengers. This capacity was put to good use to meet the military needs of Empire as we have seen. Substantial commitments to irregular trooping charters did not interrupt BI’s normal services, but not without significant rearrangements and improvisations to cover passenger ships taken off their regular run at very short notice. It is true to say no other shipping company on the oceans could have done the job the BI did.

Despite the founding of the BI in Glasgow, the head office moved to London in 1882, but Glasgow retained an engineering drawing office and was responsible for staff agreements until complete closure came in 1933. Further expansion into previously unknown waters came in 1884 with a Calcutta-Australia service. In parallel with new trading opportunities, on the technical side, the BI kept pace with developments. The second India was the first in the BI fleet to have electric light in 1881. Loodiana, later to be lost with all aboard in a cyclone en route from Mauritius to Colombo in January 1910, was the first ship to be engined with triple expansion machinery when delivered from Wm Denny & Bros in 1885.

The East Africa Connection

Although links with East Africa had been made as early as 1864, not until the mail contract between Aden and Zanzibar was agreed in 1872 did the BI have the incentive to look seriously at trading down this coast. Substantial traffic was slow to develop though. Despite poor support from the Foreign Office to counter German imperialism, British colonial interests in establishing a presence in East Africa lead to the Incoporation under Royal Charter of the Imperial British East Africa Company in May 1887. Senior BI management took up one quarter of the £240,000 share offer, and the founder William Mackinnon, was installed as President with headquarters in Mombasa. A major task was to survey the Uganda Railway from Mombasa into the interior. The I.B.E.A.C collapsed after the UK government declined to financially support the company. This failure of an organisation, lead by one of the most astute business brains of the time through lack of Government support was unfortunate. Recognition of the errors of their ways recognised. The railway eventually reached Nairobi and beyond with Government backing. Kenya, Uganda and post WWI, Tanganyika became British Terrorities.

The BI was to do very well out of East Africa over the ensuing years, trading from Bombay as a liner service, and ultimately extending to Durban as a coastal service. Later the UK-East Africa direct service became a prestige liner service. Manufactured goods from Europe went out with coconut, cloves, rare timbers, fruit, coffee, cotton and refrigerated produce returning. The Uganda Railway was eventually built with the BI carrying most of the materials and components. From Zanzibar the BI stuck out to Seychelles, Mauritius, Reunion and Madagascar putting more interconnecting red lines across the Indian Ocean, making the map appear as if covered by a spider's web.

The interest of William Mackinnon in the work of Dr. David Livingstone in Africa was such that when Livingstone’s body, carried by his followers emerged from the depths of darkest Africa and arrived at Zanzibar in 1873, it was laid out in the flat above the BI agent’s office. Passage to London for burial in Westminster Abbey was provided free of charge aboard Calcutta to Aden, from which port the P&O took over. Later in March 1887, the expedition to relive Emin Pasha was organised by the BI agent, Smith, Mackenzie. 600 native porters and stores sailed from Zanzibar round the Cape to the Congo aboard Madura at no cost.

Sir William Mackinnon, Bart, died on 22 June 1893 aged 70 in London. He is buried in the village of Clacken, in Kintyre, Argyleshire; his coffin carried on the shoulders of relays of Clackan villagers. One of the mourners was Henry Morgan Stanley. It is said he died a disappointed man after the failure of the I.B.E.A.C, Perhaps his spirits would have been raised had he seen every berth in Mombasa taken by a BI ship on 16 September 1951, seven in all. A small vessel to work on Lake Victoria was ordered by the Uganda Government, and after being hauled in pieces the 600 miles from Mombasa to Kisumu by native porters, was reassembled and launched on 4 June 1900 and named William Mackinnon. She lasted until July 1929. Spared the breakers torch, she was ceremonially sunk in the lake.

The Post Mackinnon Era

Some organisations would have floundered after the death of the founder, but not the BI. By 1894 the BI fleet had grown to 88 vessels of which six exceeded 5000 tons. It had surpassed the 100 mark of ships owned in the previous decade and a further nineteen would be delivered prior to the end of the 19th century. James Macalister Hall succeeded Mackinnon, a nephew of William in 1894. By this date the East Africa operation was based on Mombasa and service agreements with P&O to the north, and Union Castle to the south, brought mutual benefits to all three companies. With the century heading towards its close, the through London-Torres Straight-Brisbane service was withdrawn after the railway up the east coast of Australia was completed. Connecting London-Calcutta and Calcutta-Brisbane services still maintained the route with sailings fortnightly from India. An irregular Calcutta - New Zealand service started in 1896, despite a government call for transports to carry troops from India to the Sudan in support of Kitchener's retaking of Khartoum. Regular services to Japan carrying Burmese rice commenced in 1898.

For the next six years the BI found itself involved in providing troop transports (39 in all) to the Transvaal, to China to counter the Boxer Rebellion (39 ships) and to Somaliland (7 ships) plus 4 others contracted. In amongst all this, commercial activities further expanded with a Nagapatam-Penang fortnightly mail service in 1900 and in 1904 a Bombay - Karachi weekly express.

The BI policy of growing its own staff and management in 1852, and management brought the advantage of continuity. In 1874 James Lyle Mackay, born in Arbroath in 1852, came out to India as an assistant with MM&Co in Calcutta. If Mackinnon's contribution to trade is viewed as profound, the effect the future Lord Inchcape had was nothing less than seismic. His business acumen soon propelled him up the managerial ladder and by the late 1880's he was effectively the Managing Director of the managing agents. When in Bombay it was not unknown for him to ride his pony upstairs and amongst the desks, much to the astonishment of the office staff. Precedent having been set, the same trick was perpetuated in the BI club in Calcutta years later, but the startled four legged beast was left in an unsuspecting individual's bedroom.

To keep things in order, Mackay set about organising MM&Co interests in goods and services as distant from shipping whilst taking advantage of opportunities to expand as they presented themselves. Coal lands were bought in 1900, and by 1903 the number of ships owned since 1856 passed the 200 mark. Tonnages continued to rise and the largest ships were now of 6000 tons plus. An irregular Calcutta-Japan service commenced in 1907 whilst rivals on the same route, A. P. Carr, along with their coal interests were bought out in 1912. The following year, Archibald Curry & Co. Pty. Ltd. came into the BI fold. By now James Lyle Mackay had been elevated to Lord Inchcape, and in 1913 he succeeded Duncan Mackinnon as chairman and Managing Director of the BI. In December the Indian mail contracts were renewed for another ten years from 1 January 1914. Round the corner though were two events that individually would have worldwide consequences, but for different reasons.

1914: Amalgamation and War

For a long time the BI and P&O had cooperated to their mutual advantage with the BI taking mail from the P&O steamer at Aden for East Africa, Bombay for the Persian Gulf / Calcutta-Ragoon / Madras-Straits Settlements / Ceylon and all the minor Indian and Burmese ports. Each made a contribution to the other in tangible ways. Mazagon Dock in Bombay was a shared docking and repair facility, and the BI shipped coal not only for its use, but also to keep the coal dumps topped up for the P&O mail steamers which had to have security of supply. The BI provided feeder services to the P&O though out in the east.

On 27 May 1914, the day after the BI annual general meeting, right out of the blue, the BI and P&O announced a proposed merger. Nothing of this was known in the financial corridors of London as no new capital needed to be raised. Clearly, the chairman of the BI, and his opposite number at the P&O, Sir Thomas Sutherland, had arrived at the conclusion a merger would benefit both companies significantly. By October the deed was done, with the combined value of shares exchanged valued at £15,000,000 and a shipping empire in place which had a near monopoly of the main passenger and cargo lines from the UK via the Mediterranean to the east and Australia. The BI was to trade as before with its own identity and a joint board comprising twelve P&O, and eight BI directors under the chairmanship of Lord Inchcape came into play. As was said at the time "The P&O had acquired the BI, but Inchcape had acquired the P&O." As all this came to fruition a cloud settled across Europe. Of 126 ships in the BI fleet at the outbreak of World War I in August 1814, twentyfive would be lost.

To be continued in Part Two.

© Dave Mitchell 2009